Feature | Investigative \ Historic Federal Court Decision

Determination brings native title

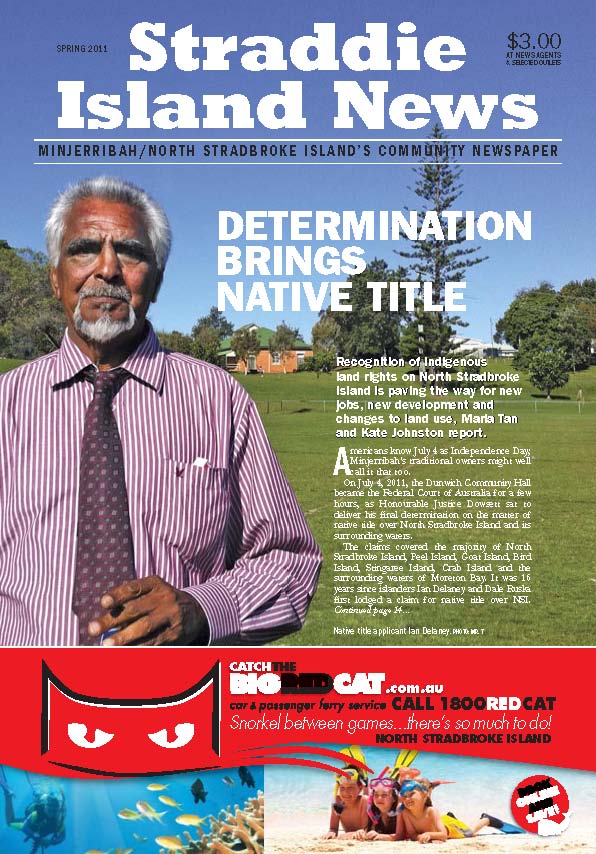

Recognition of Indigenous land rights on North Stradbroke Island is paving the way for new jobs, new development and changes to land use, Maria Tan and Kate Johnston report.

Americans know July 4 as Independence Day; Minjerribah’s traditional owners might well call it that too.

On July 4, 2011, the Dunwich Community Hall became the Federal Court of Australia for a few hours, as Honourable Justice Dowsett sat to deliver his final determination on the matter of native title over North Stradbroke Island and its surrounding waters.

The claims covered the majority of North Stradbroke Island, Peel Island, Goat Island, Bird Island, Stingaree Island, Crab Island and the surrounding waters of Moreton Bay. It was 16 years since islanders Ian Delaney and Dale Ruska first lodged a claim for native title over NSI.

It was a historic moment for Minjerribah, for Queensland and for Australia, and the first successful native title claim in southeast Queensland.

The Federal Court determination recognises exclusive native title rights and interests over approximately 2,264 hectares of land, and non-exclusive native title rights and interests over approximately 22,639 hectares of land and approximately 29,505 hectares of the Moreton Bay Marine Park.

It was a day of joy, emotion and pride – and it heralded a new future for Minjerribah; a paradigm shift in how the Island’s natural resources will be managed, how its profits will be shared, and how its Traditional Owners will be respected.

The Quandamooka people now have recognised rights including the right to live and conduct traditional ceremonies; take, use, share and exchange traditional natural resources; conduct burial rites, teach about the physical and spiritual attributes of the area; and maintain places of importance and areas of significance.

Native title claimant Ian Delaney believes the community has made the right decision. He says it is up to the younger generation to move forward. “For this to work now, everybody’s got to pull together,” he told SIN. “We’ve got a commitment from the state government that whatever we put our hand to, they’re going to support us. And I think Anna Bligh will say the same thing. And if the LNP get in next year, they’ll say the same thing,” Mr Delaney said.

For Aunty Margaret Iselin, President of the Minjerribah-Moorgumpin Elders in Council, native title rights on the Island are about recognition. “Of course you’ve gotta work with the government on all these issues and that’s how it should be,” she said. “You draw up ILUAs [Indigenous Land Use Agreements] and you have to sit down and talk, and talk, and talk to make it happen,” Aunty Margaret said.

She says those in doubt about the determination should attend consultation meetings. “They need to go along to the meetings. They need to go along and ask questions to ease their minds on what issues they want to bring up,” Aunty Margaret said. “It’s no good you being in the background and saying things and you don’t know what you’re talking about.

“It could be a good determination you know, but it means that we’ve all got to pull together on it; that’s the main thing,” she said. Redland City Council’s (RCC) North Stradbroke Island Councillor, Craig Ogilvie, told SIN there would be new plans that “will necessitate changes to the development patterns in the townships”, but that otherwise, Council’s role will not dramatically change.

“Our major role, if anything, is going to be in the land local area planning that will be done for the three townships,” Cr Ogilvie said.

“There will be some minimum levels of new development because of the determinations, but there will have to be a lot of planning done in conjunction with the community to work out what other development might happen, if any.

“The economic transition planning that is being done now is critical to making sure that we continue to exist as a community with high levels of employment and prosperity,” Cr Ogilvie said. “I’m skeptical about the potential of eco-tourism to replace mining as a source of jobs, but there is no doubt there will be some jobs [in eco-tourism] and in national park management and construction.”

One instance of new jobs will be in the running of the Island’s six campgrounds, which will move from RCC management to a corporation owned and run by the Quandamooka people. This transition has been underway for some time and can become operational now that native title has been determined.

“The new management of the campgrounds will bring a much better business focus and a big capital injection to the Island,” Cr Ogilvie said.

Redland City Council has also been establishing new planning groups, with the state government and the Quandamooka people, to tackle community consultation and future land use planning on the Island. A body corporate called the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation has been set up to manage the rights of all native title holders, while RCC and the state government have established four new groups to manage community consultation and planning for national parks, recreational reserves, township developments and land bank planning.

How the land and waters will be used under native title is set out in two Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) between Redland City Council, the state government and the Quandamooka people.

National Native Title Tribunal deputy president John Sosso told SIN the ILUAs are currently undergoing registration with the tribunal.

“They’ll be placed on a register of native title interests and will be binding on the parties for the length of the agreement. The registration of those Indigenous Land Use Agreements will result in the consent determinations made by the Federal Court [in its Dunwich sitting] becoming fully operational,” Mr Sosso said.

Mr Sosso said only general details from the ILUAs would be made public, as both contracts are commercial in confidence.

While unable to disclose details of the ILUAs, Kevin Smith, chief executive officer of Queensland South Native Title Services, legal representatives of the Quandamooka people, told SIN the agreements “could be along the lines of being able to use that land for business opportunities and broader economic opportunities.

“The land use agreement is essentially the framework to allow that. To give certainty to both parties and allow opportunities in the future to plan for the economic independence of the Quandamooka,” Mr Smith said.

One of the original applicants to the native title claim, Dunwich resident Dale Ruska, withdrew in protest in 2001 because he had lost faith in the process.

“The Aboriginal people were forced to compromise throughout the whole process. The state government would not agree to offer any benefits packages to the Quandamooka people or any compensation, unless the Quandamooka people agreed to validate all invalid acts and free the state government from any future native title compensation liabilities. That was a condition of settlement. “So the Aboriginal peoples’ hands were tied and they more or less didn’t have a say over the outcome, apart from accepting what the state government was offering,” Mr Ruska told SIN.

Spokesman for the Belgian-owned sand mining company Sibelco, Paul Smith, said the mining company had “tried to discuss an ILUA with the Quandamooka people, separate from the native title process.

“There was a lot of pressure on the Quandamooka to complete the state ILUA in order to get the native title process going, and they elected that they didn’t want to enter into a Future Acts ILUA with the company,” Mr. Smith said.

LNP State member for Cleveland, Mark Robinson, says actions by the Bligh Government have severely limited the income the Quandamooka people could otherwise have earned. “The mine was prepared to put up $28 million dollars in its own ILUA to the Quandamooka people,” Mr Robinson told SIN.

“Now that money has been largely lost because of the way that the government has locked in the legislation.” “Until they develop a planning process and the town plan, there’s a lot of uncertainty created by the ILUAs — the state and Redlands Council ILUAs,” Paul Smith said.

“A lot of people don’t understand how it [native title] works. “There’s a lot of myths and a lot of emotion and a lot of expectation that needs to be managed until people figure out how it all really works in practice,” he said.

He stressed that “differences of opinion” between Sibelco and the state government “have nothing to do with the Quandamooka people”.

“Underlying tenure is always an issue between the state and the native title holders,” he explained. “We hold mining leases and those mining leases are still granted and when we’re finished with them it’ll all go back to native title land or some other tenure.”

During consent determination celebrations at Dunwich on July 4, Premier Anna Bligh revealed that mining royalties would be paid to the Quandamooka people until mining ceases on the Island.

Ian Delaney told SIN that royalties could range between $2 million and $5 million each year until mining ceases, which he described as “peanuts”.

“Because these fellas [Sibelco] don’t earn billions of dollars, we only get peanuts actually,” he said.

Paul Smith said: “We’re not paying the Quandamooka people directly. We pay our normal royalty to the state government and they must be giving them a percentage of that.”

State Environment Minister, Vicky Darling, told SIN mining royalties would be “based upon the formula in the Aboriginal Land Act 1991, which is dependent upon the amount received by the state each financial year”.

Anna Bligh says native title rights are essentially about legal recognition of the Quandamooka people as traditional landowners. “Native title does not override freehold, people who own freehold title on the Island continue to do so,” the Premier said. “This does not in any way interrupt the title of other land holders, such as people who own homes on the Island.

“What it means is that some parts of the Island can and will be declared as Aboriginal land for the purpose of Aboriginal business. That means that national park and conservation areas can and will be jointly managed with Quandamooka people and they will have legal recognition for that. “In essence, it means a legal recognition that the Quandamooka people have always and will always be the traditional owners of this country.”